Ramon Hervey II isn’t a household name. According to Google, the most interesting fact about him is that he is the ex-husband of actress/singer Vanessa Williams. (“I’m an appendage on Google, that’s all,” he jokes.) But while Hervey isn’t famous himself, he knows fame intimately. For four decades, he has helped shepherd the careers of many famous people, serving as a manager and public relations specialist for some of the biggest names in the entertainment industry. Among them are Bette Midler, Paul McCartney, James Caan, Aaliyah, the Bee Gees, the Jacksons with Michael Jackson, Richard Pryor, Luther Vandross, Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds — and yes, Vanessa Williams.

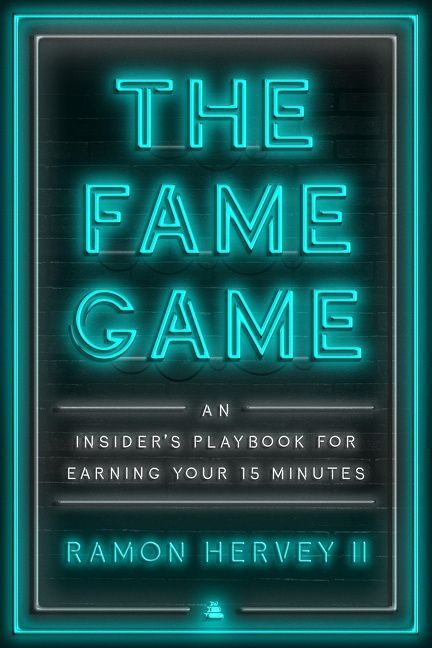

Now, Hervey is dishing on all that he’s seen, heard, and learned. In his new book, The Fame Game: An Insider’s Playbook for Earning Your 15 Minutes, he provides a rare peek into the lives of some of the biggest stars in Hollywood, using the stories as a way to impart lessons on fame — how to perceive it, manage it, and handle it when it ends.

He says he wrote the book primarily as a challenge to himself. “I spent my whole life servicing other people, either as a publicist or a manager,” Hervey tells Shondaland. “I just thought, ‘If I write, I have an opportunity to do things where I’m in control.’ I’m doing it for myself more than for other people. At this point in my life, I’d like to see what that is like.”

Hervey recently spoke with Shondaland about his career, his thoughts on fame, and how he thinks Richard Pryor would fare in today’s cancel-culture era.

SANDRA EBEJER: Why did you decide to write this book?

RAMON HERVEY II: I started to get curious about the genesis of fame and how it affected my career and all the stars that I managed or did [publicity for]. I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding about fame. A lot of people, particularly younger people, are out there trying to get so many followers on Instagram and this and that, and they don’t realize that fame is not a destination; it’s an accolade. If you’re not dedicated to your craft and you don’t work hard, it’s difficult to achieve fame. If you look at some of the bigger stars, they’ve been able to weather movies that tanked, records that tanked, but they just keep going because it’s not really about the fame. It’s about the work.

SE: In reading the book, it seems like your role was a combination of therapist, financial adviser, and parent. You’ve dealt with a lot of huge egos. What characteristics were required for you to maintain a successful career?

RH: Those three labels that you used are pretty accurate [laughs]. I have a resilient spirit, and I’m somewhat unaffected. I never put myself above or below [my clients]. My role was to create a state of calm and keep the drama out as much as I could, to be a voice of reason. Like, “Here’s the deal. We’re not going to win on this, this, and that. But I think we can win on this. Are you willing to give those things up so that we can get this?” You can’t go into any negotiation and think you’re going to win every single point. You have to be prepared to give up something so the other party feels like they’re not getting axed. That’s the game part of it. I call the book The Fame Game [because] it is a game. Everything is high risk, and there’s no guaranteed outcome. We don’t know what the public’s going to say [about a product]; we don’t know what the media is going to say. But if your heart is in the right place and you put the work in, you hope that the product will resonate. Ultimately, it’s the public who decides whether your work is worth their time or interest.

SE: I want to ask about some of the celebrities you mentioned in the book. You wrote that Richard Pryor could be “very warm and genuine, but at other times he was totally unpredictable.” How did you deal with clients who could pull the rug out from under you at any moment?

RH: You just have to be quick on your feet. With Richard, I had to have a plan A, B, C, D, and E. He never wanted people to feel he was a flake, even though he was flaking on people all the time. He’s one of the few people I worked with who somehow marketed his pitfalls in a way no one else has. When you’re a publicist, you don’t keep milking the crisis; you try to put a clamp on it and find something to draw attention [to the] work. But he didn’t do that. He used all his transgressions. He found a way to market them and make people laugh about it. People always let him off the hook.

SE: What did Bette Midler teach you about fame and how to manage it?

RH: The thing I love the most about Bette was she was a really hard worker. One of the hardest working people, if not the hardest. She never let her fame compromise her work ethic. It didn’t matter how famous she was; she wanted to go onstage every night and deliver a flawless show, which was impossible. When you do live entertainment, there’s no such thing as a perfect show. But she would strive for that every single night. And every single night after the show, she would break down every single mistake. I was [on tour] with her for three weeks, and we would sit in the limo after the show, and she would break down all these things she wasn’t happy about. She was that meticulous about her work. I think that’s what has allowed her to have a sustainable career that’s not based on just one thing. It’s allowed her to be in every medium available as an entertainer. She’s done Broadway, she’s done television, she’s done books, she’s done music, she’s toured — she’s done it all. That’s a tribute to who her character is as an artist. That’s why I adore her so much.

SE: You wrote that Little Richard seemed to be obsessed with fame, but what he actually wanted was love. How often did you come across that, where someone seemed to desire fame but was just really trying to fill an emotional hole?

RH: He never said that he wanted to be loved, but you could tell [by] the way he transformed whenever he was in front of a camera. He was a very quiet, reserved man off camera. He really didn’t talk all the time. But whenever he got an opportunity to shine, that’s when you felt like this guy just really wants to be loved. He turned on in a different way. Afterwards, he would go quiet and become almost a different person. But as soon as you got him in front of a camera, no matter what we talked about — if we had a strategy, we had bullet points of what he was going to say — I would lose him. He would just go into his character.

I think there’s a lot of insecurity in artists in terms of how they relate to fame and how much it influences them. Even Bette — she used to compare herself to a lot of people. I’d go, “Bette, there’s no one else like you. You have an edge over everybody because nobody else can do everything you can do.” But she was competitive, and when you’re competitive and maybe your project isn’t winning the way you want it to, you get [insecure]. Artists analyze their fame against other people’s fame, and that breeds insecurity. If you’re not comfortable in your own skin and you’re not pleased with your station, it can fester and undermine you. That’s when I think people start going to drugs and alcohol because they need something to sedate their anxieties.

SE: When you have a client who is on a self-destructive path, whether they’re harming themselves or others, what do you — as the publicist or manager — do to mitigate that? Can you help that person?

RH: It depends on each client. I’ve worked with several clients who had drug problems, and I told them, “If you’re going to do this, I can’t put you out in front of the media. You can’t go on a national TV show and be stoned.” I had a big problem with Natalie Cole because her manager said that she was clean, and I heard on the street she wasn’t clean. He was concerned about dates falling through because of her known drug use, so it was a money grab. She ended up being stoned and went on TV, and she made matters worse. Sometimes, they have to fall completely down before they really understand what they did. Some make it, and some don’t.

SE: What are your thoughts on fame as it exists today? It’s such a different world now than it was 30 years ago, particularly due to social media.

RH: I think we’ve jumped on a bandwagon of media platforms that are still very [young]. They’re not even teenagers yet. I mean, when you think of newspapers, radio, and even television, you’re talking about hundreds of years of media. Even though most of the [social media] platforms started in the early 2000s, it was really around 2010 when Facebook started to have an impact. So, you’re talking about 12 years. To give up your life and buy into this idea that this is the only way that you can become famous, and it’s only been out there for 12 years? I think that’s a sad statement.

I’m not all in on this being the final frontier as far as how people create and build their brands. I’m not convinced this is the only way to do it. I think some portion of this will still stay intact, but I do think it’s going to continue to change, and we just have to be prepared for it. Anyone that wants to become a star is going to have to deal with whatever the mandates are, whatever the paradigm is. It’s changed a lot since I’ve been in the business, and I think it will continue to change.

SE: You share a story in the book about a time when Richard Pryor went on a vitriolic rant against the gay community at a benefit. You write that although it hurt his career some, he “wasn’t canceled by today’s standards.” What do you think about cancel culture? How would some of your former clients fare today?

RH: That’s a good question. I definitely think if he did that today, he’d be canceled [laughs]. Particularly because [of] this whole thing with Dave Chappelle and how he’s been not completely canceled, but dates have been pulled, and people don’t want to be associated with him. [Chappelle did] close to what Richard did. It was a fundraiser for gay rights where [Pryor] made several remarks. I didn’t represent him, I represented Bette, but I was standing literally 12 feet away from him. I was on the stage seeing him do that, and then I watched him walk off the stage. I asked him about it [later] when I worked with him, and his excuse was he felt that he had been misled. He didn’t understand [the purpose of the event]. It’s a gray area in terms of whether people actually know the purpose behind these charitable events.

We live in a country where there’s freedom of speech, so I’m torn. I’ll use Dave Chappelle as an example. I think that for the right to have freedom of speech, I don’t think he should be canceled. But I also think he got his opinion out, and then he stayed on it more than he needed. He devoted hours to regurgitating the same issues and finding different ways to make his point of view, and I think that’s why he’s getting canceled. He had a choice, and I think he made a choice to push the envelope to his own liking.

I don’t think you can afford to do that if your name relies on public consumption. You have to be sensitive if you’re asking people to pay to see you or pay to support you. You become a liability to them where they’re saying, “I don’t even want people to know I like Dave Chappelle anymore, because what he did is not cool.” If you’re willing to take that risk and test your fame, you do stand a chance of being canceled. That’s what social media has done: It’s given people that maybe would never have a voice, a voice. When you empower people to use their voice, then you stand a chance of being canceled.

SE: What do you want readers to get out of this book?

RH: I hope they’ll be entertained. I’m not offering a solution; there’s no recipe [for fame]. If I could say, “Take this serum and these two vitamins, and drink water every day, and in three weeks, you’ll become famous no matter what,” I would take a shot at selling that. But the reality is, there is no [recipe]. I think you just have to be cautious when you go from anonymity to fame. Once you go down that path, your life will never be the same. The more fame you get, the more it changes your life.

The goal is to not let fame define who you are. I think for young people, that’s the thing they have to understand. It shouldn’t define you, because you’re not going to be able to sustain it at the same level your whole life. So, what do you do when you go home at night and you don’t feel famous? Or you’re not able to deal with being just a human being? I try to explain the fleetingness of fame. It can be addictive, and it’s not for everybody. Not everybody’s capable of handling it. That’s the truth.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sandra Ebejer is a New York-based writer who has contributed to The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, Greatist, Flood Magazine, and The Girlfriend from AARP. Find her on Twitter @sebejer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY