Inspired by our current exhibition, Dress Up, Speak Up: Regalia and Resistance, we reached out to local Fashion Designer Taylor Stewart to learn more about how she creates through upcycling with a passion for reducing clothing waste.

Taylor Stewart is from Dayton, Ohio and moved to Cincinnati in 2012 to attend the University of Cincinnati’s DAAP program. She graduated in 2017 with a degree in Fashion Design. At the beginning of 2018, after struggling with where she fit into the fashion industry, Taylor began developing her design practice, dedicating it to using only existing materials with no new resources.

Growing up, Taylor’s mom would take her thrifting, and luckily she said, they “lived in a neighborhood across from the best one in Dayton.” Taylor “loved the ugly, crazy, why-was-this-made garments we’d find in the racks, especially once in high school. I would experiment with fitting pieces to my body or simply hem something, and was quickly enchanted with how easy it was to customize these cheap but unique clothes. As my personal style developed, it was clear how empowering dressing oneself can be, how important having autonomy to convey one’s identity can be.” When it came time to decide a career path, it seemed like a natural choice for her to go into fashion design, not knowing what truly lay ahead.

During her time at DAAP and on co-ops, the reality of how the fashion industry behaves and negatively impacts the world became more and more apparent to Taylor. “The countless human and natural resource exploitations and violations, the detriment of mental health from unattainable beauty standards, and the constant push for newness and stimulation without any true development were just a few of the factors that left me jaded about the career I just stepped into. It was dizzying, the cognitive dissonance between seeing and experiencing all of these injustices, yet still trying to work within the industry which ultimately perpetuates them.” Taylor said that during her final internship at a fast fashion company, she “made the decision that I could not participate in the fashion industry in any conventional manner as it is today. I could not justify my role as “designer” at a company, mindlessly copying other designs (as was often asked) wasn’t worth the expense of thousands of mistreated workers. There had to be another way to harness what I loved about clothing and fashion without burning the world down.”

The first opportunity Taylor had to explore what an alternative role in the fashion realm could be, came through working with educator and designer Kaley Madden at Anti Fashion Boot Camp the summer of 2018. AFBC was an 8-week democratic community education sanctuary dedicated to reimagining clothing waste and fashion design, granted through People’s Liberty. Camp was focused on developing the “fashion ecologist” and included design workshops and fashion history lectures, not to mention the liberating photoshoots, dance parties, and radical storefront. High school students and community members were taught to collage, experiment, and construct their own collection created out of purely donated clothes. Most importantly, Kaley put an emphasis on reflection and introspection, a truly healing act in a world of constant distraction. As Taylor put it, “My time with AFBC was the most rewarding and informative fashion experience to date, better than any class I took or any co-op I worked. And it was free.”

When asked about upcycling and sustainability Taylor said, “As a resident and lover of Earth, sustainability is important to me. However, the term “sustainability” is entirely overused within the fashion industry, and I wonder if it even has meaning to companies and consumers anymore. Big clothing brands promote “sustainable collections” or organic/recycled fibers and take-back programs, while still pumping out an unholy number of garments, sucking up natural resources and being produced in poor working conditions. These unsubstantiated claims mislead consumer’s perceptions of a company’s products and practices. Consumers also donate their unwanted clothing items at ever increasing rates, blindly believing they are doing a good deed. In reality most donated clothing is not resold, but rather shipped to the global south at unmanageable rates and ultimately end up in places where clothes should not be (mountainous landfills, stomped into the soil, the ocean). We’ve all heard the “reduce, reuse, recycle” slogan ad nauseam, but only seem to focus on the “recycle” and pretend that is enough to tackle the waste problem. It’s not. The practice of upcycling, reworking existing garments, addresses the other sides of the green triangle; it reduces consumption of new and reuses the goods we already have.”

“Upcycling means so much more than just sustainability to me. Our society has been conditioned to see our clothes as completely disposable, drained of any value after a month or two. We are so disconnected from our clothes that we fail to maintain empathy with them. If you’ve ever made a garment, you understand all the cutting, pinning, turning, pressing, sewing, fitting and finessing that needs to go into a creation. A bit of your soul goes into that piece, you cherish it, flaws and all. Now, what if we could pay respect to the craft of the workers producing clothes by not immediately throwing them in a landfill? What if we could pay respect to the resources harvested by actually using them? Upcycling can do both. Let your goods keep telling their story after the first chapter. My goal is to show and inspire others to actually love what they put on their body and to make their clothes last.”

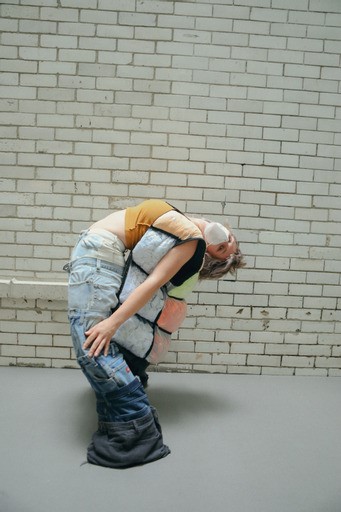

The upcycling practice itself is seriously so rewarding. Taylor’s first example – the sourcing. “This can be absolutely anywhere; you can start with your closet, your grandma’s closet, the thrift store – I’ve picked things up out of the street before. With social media it’s easy to put out a call for garments and more often than not the donation response is more than one can really handle. Finding treasures amongst others’ trash is a rush I’ve been chasing for years.” Next comes the breakdown of the garments. “Once you have materials you connect with, the deconstruction can begin, always my personal favorite. It can be daunting to chop into an otherwise fine garment, but you have to trust the process, some Bob Ross happy accidents mantras.” After all the parts are laid out, the process of collaging them together begins. “I do “sketching” by mixing and safety pinning parts around until I find something I like.” And finally, it all needs to get sewn together. “No need to follow stuffy, proper sewing techniques, just slap some stitches where they need to go. There’s a lot of back and forth of pinning and sewing, this step feels more like sculpting than anything. Then throw it on and strut! There is something viscerally satisfying about transforming trash into something of high value. Not only has this practice taught me patience and flexibility with my design work, but also compassion and healing with the world around me.”

Understandably, Taylor’s clothes aren’t for everyone, and that is very okay by her. As she puts it, “I’m not driven by mass production and maximizing profits, or by the latest trends in celebrity fashion. They aren’t the vanilla cookie cutter outfits from fast fashion stores, they aren’t born of perfectionism that dominates American culture.” Instead she makes what she wants to see, what she wants to experiment with, and hopes it resonates with someone. “I want the clothes I make to have character and personality and be unconventional… they’re one of a kind. I make clothes for people who LOVE clothes, not just wearing clothes. I make clothes for people who want to shop outside the exploitative system that is fashion today. Most importantly, I make clothes for people looking to challenge beauty norms and to define their individualized expression of beauty. As I move into more of a made-to-order model, I want to be the avenue for people to explore what ‘self-actualization through dress’ can be. I believe we need to shift the narrative of top-down “fashion genius” and give voice and power directly back to the consumers, rather than holding them hostage in the same stuffy ideas.”

Follow Taylor at @babysteww to keep up with her work!