You can almost see the involuntary twitch of a chill coursing through him. “It really was a childhood trauma for me,” Noah Baumbach says. “It has come up in therapy my entire life. It really messed me up. It messed me up.”

For an instant, you assume, understandably, that Baumbach is talking about the divorce of his parents, film critic Georgia Brown and experimental novelist Jonathan Baumbach, back in the 1980s. But it’s not that simple. Baumbach is actually talking about going to see Invasion of the Body Snatchers—the creeped-out, dread-soaked 1978 version starring Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams, and Jeff Goldblum—when he was a kid in Brooklyn, just as the torn seams of his parents’ marriage were becoming visible. “The notion of people seeming the same but not being what they present themselves to be was very scary to me,” Baumbach goes on. “I think I picked up on that through Body Snatchers. The concept of it just scared me so much. . . . I was probably nine at the time.”

The idea of using a horror flick to process the toxic convolutions of divorce makes perfect sense when it comes to Baumbach, a die-hard movie freak who, at fifty, has patiently built up a body of cinematic work that qualifies him as a poet laureate of marital strife. No, his directing career didn’t begin with 2005’s The Squid and the Whale (it got going a decade earlier with the slackers-stuck-in-neutral tropes of 1995’s Kicking & Screaming, after which Baumbach himself got stuck in neutral for a spell), but a lot of people think of Squid as the movie in which a specifically Baumbachian view of the world really started to jell.

Squid was a divorce movie; his new one, Marriage Story, is a divorce movie, too. And it’s one that hinges on the realization Baumbach had back when Invasion of the Body Snatchers put a fresh coat of frost on his young bones: the idea that people might not be what they appear to be. For anyone, like me, who has ever endured a divorce, watching Marriage Story is simultaneously harrowing, heartbreaking, and thrilling. Thrilling because of everything that Baumbach gets right: the nauseating parabola swoops of emotion, the flirtations with bankruptcy, the austerity of a single dad’s apartment, the strained pantomime of solo parenting, and the grim theater of finding yourself legally pitted against the person with whom you’ve spent years building a home. The movie reminded me of “Failing and Flying,” a poem by Jack Gilbert that touches on a paradox of divorce—the way the end of a relationship seems to devour the beginning. “Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew,” Gilbert writes. “It’s the same when love comes to an end.”

Divorce forces you to think back to the beginning, when you met someone and a life together seemed full of promise, and to gulp down the bitterness of how much has changed along the way. Marriage Story opens with love letters, or lines that sound as though they’re from love letters, being recited in tandem by a married couple, Scarlett Johansson’s Nicole and Adam Driver’s Charlie. But the context of those epistolary odes abruptly shifts, and shifts again, as Baumbach comes to reveal the chasm that stretches between Nicole and Charlie. Pretty soon they’re both sucked into the scream-inducing, I-don’t-even-know-who-you-are frightfest of a full-throttle split, and no matter how hard they try to stick to their original script and opt for the serenity of conscious uncoupling, legal and logistical challenges wind up turning them into raging beasts. Can they avoid becoming pod people? If we still happened to be living in 1978, the poster for Marriage Story would probably say something like: “They’ll never get through divorce without each other.”

Comradeship among those of us who have experienced divorce that’s akin to the bond between soldiers who exchange stories about the agonies of boot camp. You’d think it would be more comfortable to avoid the war stories, whether in conversation or onscreen, but of course it’s a relief to get them out. “That’s what I love,” says Johansson, who has been through divorce twice. “I love to pick all that stuff apart. That’s the good stuff.” And watching people hash out a divorce for two hours and sixteen minutes may sound like sipping a bowl of lemon-juice soup, especially for anyone who has experienced it, but it’s a testament to Baumbach’s dexterity as a filmmaker that he keeps re-upping your attention with deft jolts in tone. Marriage Story is full of surprises.

There are musical interludes that somehow don’t feel the slightest bit forced. (It turns out that Adam Driver really can sing.) There are guest stars who confirm all the received wisdom about the importance of casting. (Laura Dern and Ray Liotta’s next move should be a Netflix series about divorce lawyers.) There’s a screaming match terrifying enough to make all the costumed punch-and-kick ballet of the Marvel universe look like child’s play (which, after all, it is). And yet the perspectives of Nicole and Charlie get equal time in the spotlight. “We’re very much with both of them,” Baumbach says. “There’s no side to take. It can still be a love story even if they don’t end up together.” So, yeah, Marriage Story amounts to a drama / thriller / slasher / musical / rom-com about two people finding a way to love each other through a labyrinth of existential fog, courtroom maneuvering, and hate, and it might just represent Noah Baumbach’s crowning achievement after a few decades on the job.

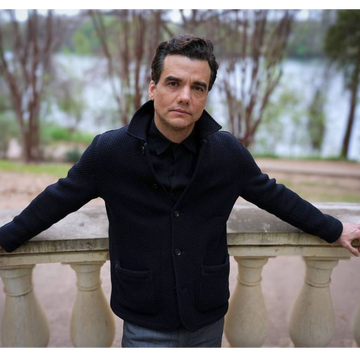

Baumbach shows up early for a late lunch at one of his downtown Manhattan haunts, Bar Pitti. He’s wearing a black polo shirt that seems to complement his still-thick Kennedyesque swoop of inky hair. He comes across as a dashing, stammery remnant of a downtown New York that’s gradually being gentrified out of existence—an ecosystem of Gotham creatives loafing, kvetching, flirting, pitching. He shares an apartment with Greta Gerwig, the writer and director and actor who had her own zeitgeist moment two years ago with Lady Bird. They collaborated on the screenplays for Frances Ha and Mistress America; they collaborated, too, on a child who was born last March. They aren’t married yet, at least not at the time of this particular lunch at Bar Pitti, but they’re not averse to the idea. “We just have to go do it,” Baumbach says. “We’ve been engaged for a long time.”

You wouldn’t blame him for being a little circumspect about marriage, a little leisurely on his way to the altar, considering the way divorce looms in his mind. He has endured not only the split of his parents but also his 2013 break (after three years of separation) from actor Jennifer Jason Leigh. There are, naturally, echoes between Marriage Story and Baumbach’s own marriage story—he and Leigh have a son together named Rohmer, and Baumbach has a second home in Hollywood so he can visit—but you’d be naive to think he’s going to draw you a map so that you can find all the buried references.

Nevertheless, Marriage Story is so precise in its depiction of a split, joining 1979’s Kramer vs. Kramer and 2010’s Blue Valentine in the annals of great love-is-a-bummer flicks, that I find my conversation with Baumbach becoming part interview, part ad hoc therapy session. There is the knowing nod when I tell him that I’ve experienced divorce too, and more meaningful nods ensue when we talk about becoming fathers again at midlife. Baumbach projects like Kicking & Screaming, Frances Ha, and While We’re Young have meant a lot to me over the years, but with Marriage Story he seems to have struck, for me at least, some kind of personal bull’s-eye. I tell Baumbach about the Jack Gilbert poem, and I tell him that a friend of mine once described divorce as “waking up every day and getting punched in the face.” Hearing that, he reveals faint traces of a smile.

But by now, my divorce talk with Noah Baumbach probably has the ring of the familiar. To prepare for writing Marriage Story, he spent months interviewing friends about their own marital fractures. He compares it to spending sustained time in a hospital with a dying relative. “When you’re in it, it absolutely takes over your life,” he says. “When it’s over, you don’t want to hear from it. . . . The system is designed, in a way, to pit you against each other.” He did the reportorial legwork in part so that he could fill Marriage Story with all sorts of odd details that help illustrate divorce in all its brutality and banality. During one scene in the movie, legal advisors suddenly take a break from a tense session with Charlie and Nicole so that they can choose salads and sandwiches from a delivery menu. “I wanted them to order lunch during the mediation,” Baumbach says. “The quotidian is everything in the moment, really.”

But those moments of tedious absurdity set the stage for torrents of venting, singing, and bloodletting—both emotional and, in one scene, literal. If Johansson and Driver get Oscar nominations for their performances in Marriage Story, voters will undoubtedly be thinking of a tableau vivant, set in a stark Los Angeles apartment, in which Nicole and Charlie try to sit down and settle things in a civilized manner, only to find themselves swept away in escalating riptides of rage. It’s a spat that makes Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? look like an etiquette lesson. After you’ve watched it, keep in mind that Baumbach is a director who likes to shoot a lot of takes. Filming that fight went on for two straight days. “It’s the only time that I’ve lost the required distance as a director,” he says. “I’d have to walk around the block to clear my head. . . . It was exhausting.” During breaks, the director and his actors would retire to other rooms in the apartment building to decompress. “He will exhaust it until you think you have no ideas left,” Johansson says—and then, in that moment of surrender, the right, raw take will emerge.

Yet that scene, which comes across as a study in the volatility of losing control, is in fact an example of control at its most granular. Adam Driver describes Baumbach as a micromanager, sure, but in a positive way. “Whether it be with actors, scheduling, what the set design should feel like, or what the clothes should be or feel like, he knows his job and can articulate his thoughts with absolute clarity,” Driver says. “You’re not gonna change a word of dialogue, and you’re gonna want to say it over and over again.”

As Baumbach reveals with his Invasion of the Body Snatchers anecdote, he uses movies as a way to absorb and understand life as it unfolds. In conversation at Bar Pitti, he sounds like an excitable film professor at a prep school, name-checking directors like Mike Nichols, Paul Mazursky, Peter Bogdanovich, Philip Kaufman, and Ingmar Bergman in the span of time it takes to finish off a bowl of lentils. His attachment to the pantheon of Hollywood renegades strikes you as simultaneously charming and antediluvian. (Driver puts it this way: “He was raised with this idea of art as religion, but it’s also in his nature.”) Does anyone remember the stuff that these people did—films like Persona and The Last Picture Show and An Unmarried Woman? Hasn’t all of that been washed away in an inexorable flood of superheroes? And where does a storyteller like Noah Baumbach even belong at this point? Lately his friends have been telling him, “You’re supposed to be on a downswing now.”

But here he is at fifty, the very model of a Gen X creative at midlife, having made arguably his best film and stunned to be looking back at a quarter century of work. “It’s really gratifying to realize I’ve been doing this that long,” he says. “To make the movies that I want to make, that are meaningful to me . . . I feel more at ease than I did when I started.” His generational cohort in Hollywood may’ve been a pack of hares: Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson, M. Night Shyamalan. But Baumbach’s approach has been that of the tortoise, taking his own sweet time making movies about human beings, bereft of tricks or frills.

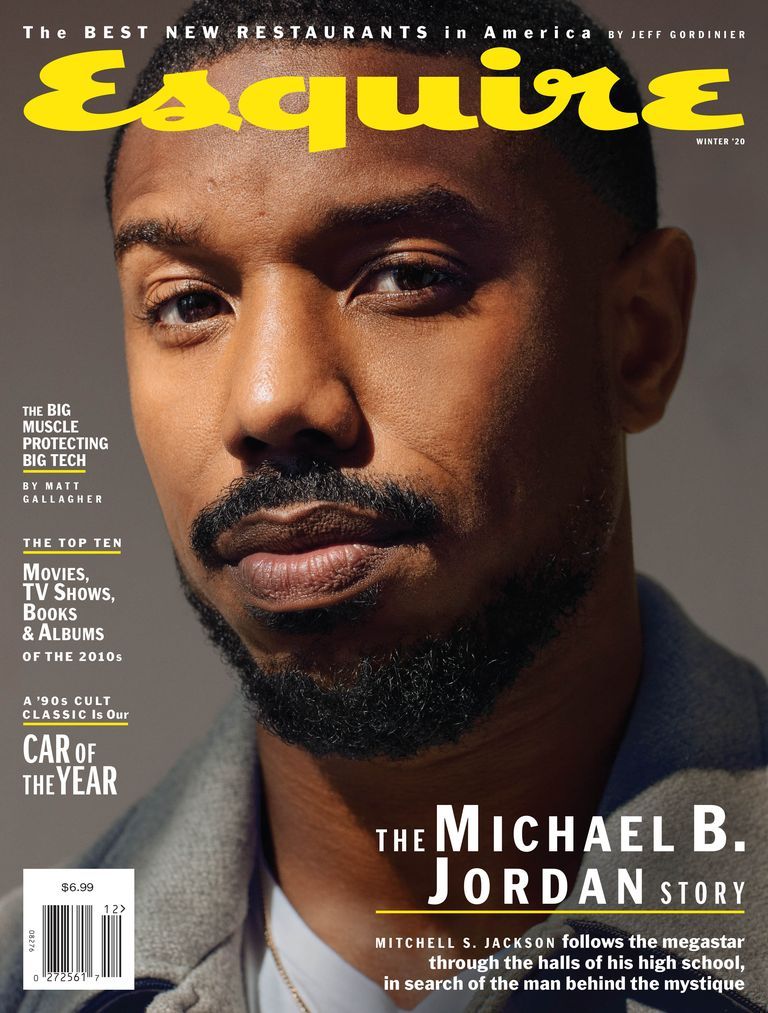

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue of Esquire

Subscribe

You might even compare the American movie landscape in 2019 to, yes, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, with wave after wave of cool indie actors and directors forsaking their Sundance cred overnight and morphing into pod people, unrecognizable versions of themselves, all too happy to cash in with one dumb blockbuster franchise after another. Could Gerwig and Baumbach be among the last of the true believers, typing away together in their Greenwich Village apartment, presumably trading quips like Nick and Nora in the Thin Man flicks? Or will Baumbach’s bittersweet wellspring of interpersonal drama run dry, forcing him to succumb to directing Baby Spider-Man 3: From the Cradle to the Grave?

He winces and smiles.

“Wellll,” Baumbach says. “I have a lot of material. I haven’t run out.”