Editor’s Note: Michael S. Roth is the president of Wesleyan University. A historian, he was formerly the president of the California College of the Arts. His most recent books are “Safe Enough Spaces: A Pragmatist’s Approach to Inclusion, Free Speech and Political Correctness on College Campuses” and “Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters.” The views expressed here are his. Read more opinion on CNN.

Every age seems to need a bogeyman, some negative image against which good people measure themselves. When I entered college in the mid-1970s, the term “welfare queen” was being popularized by Ronald Reagan as he campaigned for president and was starting to be taken up by the mass media. It would soon go on to upstage the outworn “commie” and well-worn “dirty hippie” as objects of vitriol in the American political imagination. Self-described regular, decent Americans had in “welfare queen” a new image against which to define themselves.

There had long been accounts of people scamming the government in one way or another – contractors overcharging, politicians on the take, crooked cops. But the trope of the “welfare queen” was nicely constructed to seep into a white American psyche already anxious in the 1970s and 1980s about race, single mothers and an urban culture that challenged more than a few mainstream myths.

Today I am a college president and a teacher at a school known for student activism, and I’ve noticed a new trope on the scene with rising potential as a national scapegoat. It’s the politically correct, “woke,” college student. If the sins of the welfare queen were crafty laziness and promiscuity, the sins of the woke so-called social justice warrior are elitist condescension and a failure to connect with the needs of real people.

Like the welfare queen, the woke student activist is a convenient type – one who unites others in opposition to what they imagine is wrong with this country. And just as welfare cheats attracted criticism from Republicans and Democrats alike from the Reagan years through the Clinton administration’s welfare reform plans in the 1990s, so woke young people have aroused the choreographed indignation of leaders as different as Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama.

Trump realized the power of being anti-PC somewhere between his guest appearances on the Howard Stern radio show and his run for the presidency: no matter what he said or did, he could take the high ground, or at least earn credit, for not being politically correct.

In one of the early debates in the 2016 election, Megyn Kelly questioned the candidate about his demeaning comments about women over the years. “I think the big problem this country has is being politically correct,” he replied (to applause from the audience). Throughout the election, he turned what might have been judged as moral lapses into heroic refusals to conform to politically correct moral criteria. And he’s doubled down on this move repeatedly since taking the oath of office.

Every president since the first George Bush has earned points by attacking political correctness and last month Obama joined in, receiving kudos for admonishing young people to stop trying to be holier than thou in their political righteousness. During an interview at the recent Obama Foundation summit, Obama said, “I do get a sense sometimes now among certain young people, and this is accelerated by social media, there is this sense sometimes of: ‘The way of me making change is to be as judgmental as possible about other people,’ and that’s enough.”

He drew praise from across the political spectrum in concluding: “That’s not activism. That’s not bringing about change…If all you’re doing is casting stones, you’re probably not going to get that far. That’s easy to do.”

Yes, that is easy to do. Denouncing college students – be they the long-haired protestors of the 1960s, the environmentalist “tree huggers” of the 1990s or the “pronoun policers” today – is bound to please in a number of circles. Like the welfare queens of yore, the stereotype of the woke social justice warrior, only concerned with canceling other people, is a politically useful (if wildly misleading) figure. Nobody wants to fit this description, and in my experience, very few actually do.

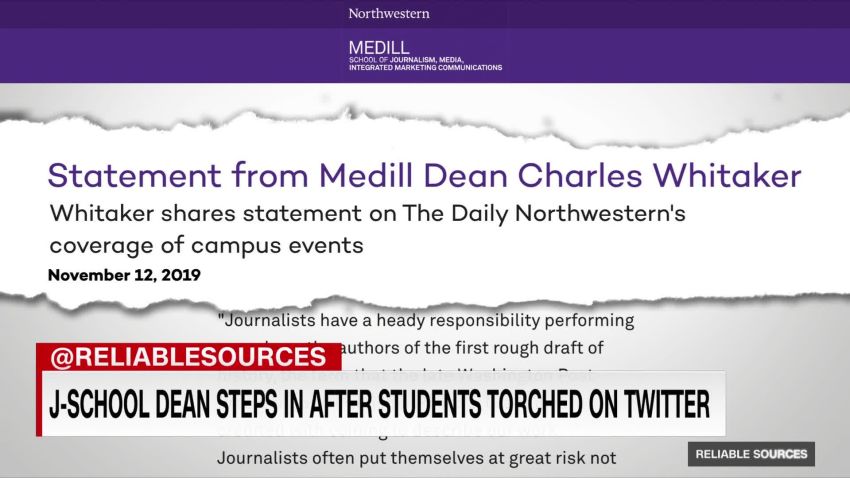

Sure, there are cases of student protestors who angrily denounce practices that previous generations thought were emblematic of fairness or free expression. Student newspapers at Northwestern and Harvard were criticized within the last month–for soliciting a statement from ICE, in the case of the Harvard Crimson, and for tracking down student activists for their statement on a disruptive protest, in the case of the Daily Northwestern.

In both cases, some of the young journalists were taken off guard and wanted to apologize to their fellow students on the left. They were quickly pounced upon by pundits, while less attention was paid to those other students at the newspapers who defended the young journalists’ reporting practices and their editorial autonomy. It turns out there was a healthy debate in newsrooms after all.

Conversations about race, the economy, bias, sexual assault, climate change or the winner-take-all economy all tend to involve strong emotions and challenging complexity. Sometimes, people complain that they don’t want to speak up because they fear being criticized or stigmatized. But they should recognize that their fear isn’t somebody else’s fault – isn’t a sign of their environment’s political correctness or hostility toward free expression. Their fear of speaking out is just a sign that they need more courage — for it requires courage to stay engaged with difference.

The images of the welfare queen and of the woke student are convenient because they provide excuses to not engage with difference, placing certain types of people beyond the pale. These scapegoats are meant to inspire solidarity in a group by providing an object for its hostility (or derision), and educators and civic leaders should not play along. Instead of arousing easy antipathy, they should strive to cultivate the robust exchange of ideas across differences. In the year leading up to the next national elections, these exchanges are more important than ever.

We desperately need young people to assume their civic responsibilities, and universities have a responsibility to help them to do so. Over the next 12 months, I am optimistic that we will see the activism of college students refute the charge that their politically correct generation just cancels others, or that it is self-satisfied in its condescending “wokeness.” That charge serves only the status quo, and the continuation of the status quo today would mean a very bleak tomorrow.

Educators and pundits should stop whining that young people aren’t what they used to be and start cultivating civic preparedness. Students can reject the tired tropes of the past and embrace what many in the older generations have forgotten: how to build effective coalitions with people who have a variety of points of view, and who imagine the future with a mix of hopes sometimes very different from their own. No bogeymen required.